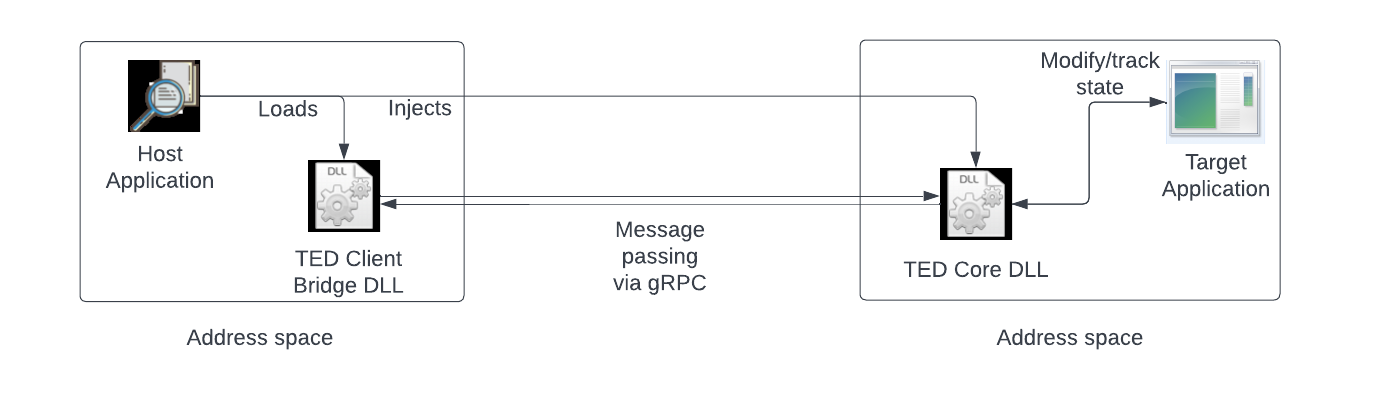

TED is a limited general purpose reverse engineering API, and hybrid debugger, that allows for inspection and modification of a program’s inner workings. TED carries out its functionality by being injected into a target process and starting a gRPC server, which clients can then connect to. There are a large set of services available to perform typical operations such as enumerating loaded modules, reading and writing memory, enabling and disabling breakpoints, disassembling address ranges, loading and unloading other modules, and more.

From a high level, TED works as follows:

A host application is responsible for loading the TED Client Bridge DLL, which has a set of APIs that handle client message building and server response parsing. After the Client Bridge DLL has been successfully loaded, the host application can use a helper API to inject the TED Core DLL into a target application. Assuming the DLL injection happened successfully, the Core DLL will launch a gRPC server listening on localhost:50051. The client can then invoke desired gRPC services and have them execute in the context of the target application. Service definitions are provided in a TED.proto file; they are either basic request-response, or a streaming service for receiving breakpoint events and their associated information.

After the client and server have both been loaded successfully, performing communication between the two is rather straightforward. The host application will create a client connection to the underlying server via a TED_CreateClient call. This will return an opaque handle to the caller that will then be passed to all subsequent APIs. Once the host application is done with the connection, it can call TED_DestroyClient to officially close the connection and clean up. This patterns follows for the rest of the APIs; all APIs that return a response have a corresponding TED_DestroyX API that will clean up allocated memory.

The code snippet below demonstrates injecting the TED Core DLL into another process, creating a client to establish communication, and receiving a response from the server that contains information about all loaded modules in the target process.

// Load client API and resolve functions

auto moduleHandle{ TED_LoadClientAPI("TEDClientAPI.dll") };

TED_ResolveClientFunctions(moduleHandle);

// Get process id of target

DWORD targetProcessId{};

GetWindowThreadProcessId(FindWindow(nullptr, L"Untitled - Notepad"), &targetProcessId);

// Get full path of TED Core DLL so that target process can load it

std::array<char, MAX_PATH> currentDirectoryPath{};

auto size{ GetModuleFileNameA(nullptr, currentDirectoryPath.data(), MAX_PATH) };

std::string coreDllPath{ currentDirectoryPath.data(), size };

coreDllPath = coreDllPath.substr(0, coreDllPath.find_last_of("\\")) + std::string{"\\TEDCore.dll"};

TED_InjectIntoProcess(targetProcessId, coreDllPath.c_str());

// Create the client

auto client{ TED_CreateClientFnc("localhost:50051") };

// Get the modules

auto response{ TED_GetModulesFnc(client) };

// Enumerate over the response

for (size_t i{ 0 }; i < response->moduleInfoCount; i++) {

const auto* moduleInfo{ response->moduleInfo[i] };

std::cout << std::format("Module name: {}\tModule base address: {:X}\tModule size: {:X}",

moduleInfo->name,

moduleInfo->baseAddress,

moduleInfo->size)

<< std::endl;

for (size_t j{ 0 }; j < moduleInfo->executableSectionCount; j++) {

const auto* executableSection{ response->moduleInfo[i]->executableSections[j] };

std::cout << std::format("Section: {}\tSection base address: {:X}\tSection size: {:X}",

executableSection->name,

executableSection->address,

executableSection->size)

<< std::endl;

}

}

// Clean up modules response

TED_DestroyModulesFnc(response);

// Clean up client

TED_DestroyClientFnc(client);Running this code while having Notepad open will produce the following output:

Module name: C:\Program Files\WindowsApps\Microsoft.WindowsNotepad_11.2208.25.0_x64__8wekyb3d8bbwe\Notepad\Notepad.exe Module base address: 7FF60B660000 Module size: 84000

Section: .text Section base address: 7FF60B661000 Section size: 49C00

Module name: C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32\ntdll.dll Module base address: 7FFF70250000 Module size: 214000

Section: .text Section base address: 7FFF70251000 Section size: 12D000

Section: PAGE Section base address: 7FFF7037E000 Section size: 1000

Section: RT Section base address: 7FFF7037F000 Section size: 1000

Section: fothk Section base address: 7FFF70380000 Section size: 1000

Module name: C:\WINDOWS\System32\KERNEL32.DLL Module base address: 7FFF6EC80000 Module size: C2000

Section: .text Section base address: 7FFF6EC81000 Section size: 80000

Module name: C:\WINDOWS\System32\KERNELBASE.dll Module base address: 7FFF6DCB0000 Module size: 39C000

Section: .text Section base address: 7FFF6DCB1000 Section size: 189000

...As a quick aside to the above code snippet, the memory management can be made more simple. Since the client APIs are exported with C linkage, there need to be corresponding cleanup functions for memory that gets allocated during a request-response flow. However, in a host application, these can be wrapped with smart pointers to ensure that no memory will get leaked. Below is an example of this, and is the preferred way to develop against the library:

// Create the client

std::unique_ptr<TED_Client, TED_DestroyClientFncPtr> client{

TED_CreateClientFnc("localhost:50051"),

TED_DestroyClientFnc };

// Get the modules

std::unique_ptr<TED_GetModulesResponse, TED_DestroyModulesFncPtr> response{

TED_GetModulesFnc(client.get()),

TED_DestroyModules };

// "client and "response" memory will be freed when they go out of scopeThe next example shows how to set a breakpoint and subscribe for a streaming response from the server. This will set a breakpoint on a commonly used function in UI applications: DispatchMessage. When this function is executed, the server will capture information about the program’s state, and send it to the client. The client then prints out the results to the console. Since the service returns a streaming response, the client continues to listen to the stream and prints out messages as they come in. On the server, there is a persistent connection established and breakpoint information events are sent to the clients as they are received.

// Load client API and resolve functions

auto moduleHandle{ TED_LoadClientAPI("TEDClientAPI.dll") };

TED_ResolveClientFunctions(moduleHandle);

// Get process id of target

DWORD targetProcessId{};

GetWindowThreadProcessId(FindWindow(nullptr, L"Untitled - Notepad"), &targetProcessId);

// Get full path of TED Core DLL so that target process can load it

std::array<char, MAX_PATH> currentDirectoryPath{};

auto size{ GetModuleFileNameA(nullptr, currentDirectoryPath.data(), MAX_PATH) };

std::string coreDllPath{ currentDirectoryPath.data(), size };

coreDllPath = coreDllPath.substr(0, coreDllPath.find_last_of("\\")) + std::string{ "\\TEDCore.dll" };

TED_InjectIntoProcess(targetProcessId, coreDllPath.c_str());

// Create the client

std::unique_ptr<TED_Client, TED_DestroyClientFncPtr> client{

TED_CreateClientFnc("localhost:50051"),

TED_DestroyClientFnc };

// Create the reader

std::unique_ptr<TED_BreakpointReader, TED_DestroyBreakpointReaderFncPtr> reader{

TED_CreateBreakpointReaderFnc(client.get()),

TED_DestroyBreakpointReaderFnc };

// Set a breakpoint on a DispatchMessageW

std::unique_ptr<TED_GenericResponse, TED_DestroyGenericFncPtr> breakpoint{

TED_EnableBreakCallByAddressFnc(client.get(), (uint64_t)DispatchMessageW),

TED_DestroyGenericFnc };

while (true) {

std::unique_ptr<TED_BreakpointResponse, TED_DestroyBreakpointFncPtr> response{

TED_GetBreakpointFnc(client.get(), reader.get()),

TED_DestroyBreakpointFnc };

if (response != nullptr) {

std::cout << "Read breakpoint event\t"

<< std::format("Process ID: {}\tThread ID: {}\tSource Address: {:X}\tDestination Address: {:X}",

response->processId, response->threadId, response->sourceAddress, response->destinationAddress)

<< std::endl;

std::cout << "Context: \n";

// Output context information here (see proto definition)

std::cout << "Call stack: \n";

if (response->callStack.stackFramesCount > 0) {

for (size_t i{ 0 }; i < response->callStack.stackFramesCount; i++) {

const auto* stackFrame = response->callStack.stackFrames[i];

std::cout

<< std::format("RIP:{:X} Return Address:{:X} Frame Pointer:{:X} Stack Pointer:{:X}",

stackFrame->rip,

stackFrame->returnAddress,

stackFrame->framePointer,

stackFrame->stackPointer)

<< std::format(" Param 1:{:X} Param 2:{:X} Param 3:{:X} Param 4:{:X}",

stackFrame->parameters[0],

stackFrame->parameters[1],

stackFrame->parameters[2],

stackFrame->parameters[3]);

if (stackFrame->symbols.functionNameLength > 0) {

std::cout << " " << stackFrame->symbols.functionName;

}

std::cout << std::endl;

}

}

}

}Running the above code will produce the following output:

Read breakpoint event Process ID: 78648 Thread ID: 73480 Source Address: 7FFF6EE17A20 Destination Address: 7FFF6EE17A22

Context:

Call stack:

Read breakpoint event Process ID: 78648 Thread ID: 73480 Source Address: 7FFF6EE17A20 Destination Address: 7FFF6EE17A22

Context:

Call stack:

Read breakpoint event Process ID: 78648 Thread ID: 73480 Source Address: 7FFF6EE17A20 Destination Address: 7FFF6EE17A22

Context:

Call stack:The output should flood the screen as you scroll through the Notepad UI since DispatchMessage will be constantly invoked. As the output seems to hint at, it is possible to get context and call stack information back to the caller. This can be done by setting the appropriate options to have the Core DLL return this information back to the client.

// Set options

TED_Options breakpointOptions{};

breakpointOptions.returnCallStack = true;

breakpointOptions.returnContext = true;

breakpointOptions.returnSymbolInfo = true;

std::unique_ptr<TED_GenericResponse, TED_DestroyGenericFncPtr> options{

TED_SetOptionsFnc(client.get(), &breakpointOptions),

TED_DestroyGenericFnc };After setting these options and re-running, the output contains call stack and symbol information:

Read breakpoint event Process ID: 59016 Thread ID: 16644 Source Address: 7FFF6EE17A20 Destination Address: 7FFF6EE17A22

Context:

Call stack:

RIP:7FFF6EE17A22 Return Address:7FF60B6794D5 Frame Pointer:0 Stack Pointer:12748FFC68 Param 1:15D25B5 Param 2:15D25B5 Param 3:12748FFCD9 Param 4:0 DispatchMessageW

RIP:7FF60B6794D5 Return Address:7FF60B6A5DBA Frame Pointer:0 Stack Pointer:12748FFC70 Param 1:1 Param 2:1 Param 3:0 Param 4:0

RIP:7FF60B6A5DBA Return Address:7FFF6EC9244D Frame Pointer:0 Stack Pointer:12748FFD40 Param 1:0 Param 2:0 Param 3:0 Param 4:0

RIP:7FFF6EC9244D Return Address:7FFF702ADF78 Frame Pointer:0 Stack Pointer:12748FFD80 Param 1:0 Param 2:0 Param 3:0 Param 4:0 BaseThreadInitThunk

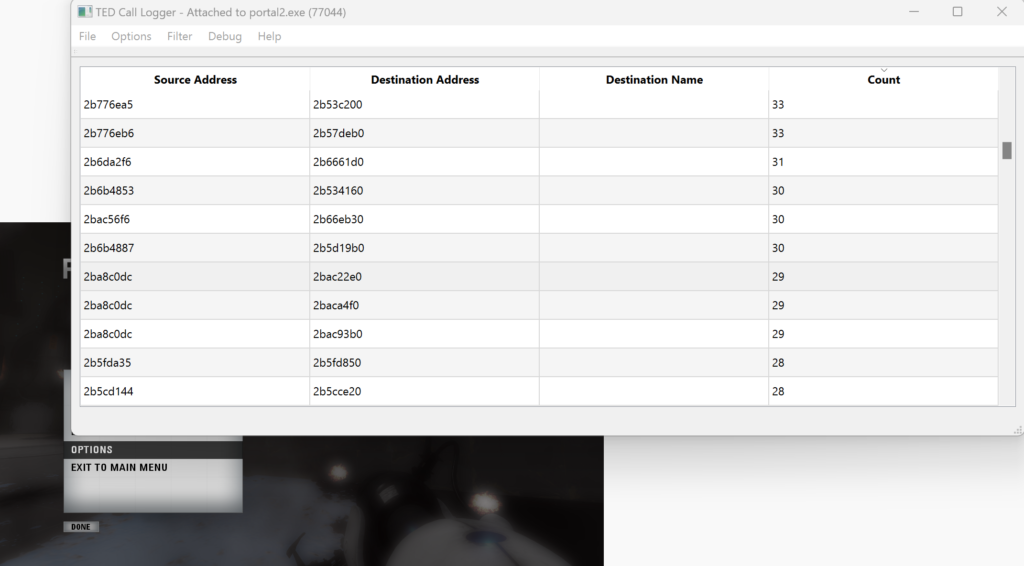

RIP:7FFF702ADF78 Return Address:0 Frame Pointer:0 Stack Pointer:12748FFDB0 Param 1:0 Param 2:0 Param 3:0 Param 4:0 RtlUserThreadStartTo show some of the power of the TED API, I have developed a client application that will log all CALL instructions that a target application executes. I then used this application against Portal 2, attaching to client.dll, with the goal of finding the code that is executed when a player shoots their portal gun.

To do this, I first set the Call Logger application to automatically disable incoming breakpoints (Options -> Auto disable incoming from the menu). This allows you to filter out irrelevant events – and there will be plenty – when searching. After clearing the breakpoints window (Filter -> Clear from the menu), running around in-game, clearing again, going back to the game and running around again, I got to a point where most of the irrelevant breakpoints were automatically disabled and the breakpoints window was not being flooded with new rows.

At this point, I turned off the auto disable functionality, and began shooting the portal gun in the game. In the breakpoints window, I tracked the hit counts of source addresses and found those that incremented by one when I shot the portal gun. Right clicking a row and selecting “Copy addresses” from the context menu gave me the appropriate address information:

Source: 0x2ba8c0dc (client.dll+0x59c0dc) Destination: 0x2bac93b0 (client.dll+0x5d93b0)The next step is to restart Portal 2, attach x64dbg to it, and navigate to client.dll+0x59c0dc. Doing so gets you to the following place:

2E22C0C7 | 8B4D 18 | mov ecx,dword ptr ss:[ebp+18] |

2E22C0CA | 8B55 14 | mov edx,dword ptr ss:[ebp+14] |

2E22C0CD | 8B06 | mov eax,dword ptr ds:[esi] |

2E22C0CF | 51 | push ecx |

2E22C0D0 | 8B4D 08 | mov ecx,dword ptr ss:[ebp+8] |

2E22C0D3 | 52 | push edx |

2E22C0D4 | 8B50 74 | mov edx,dword ptr ds:[eax+74] |

2E22C0D7 | 53 | push ebx |

2E22C0D8 | 57 | push edi |

2E22C0D9 | 51 | push ecx |

2E22C0DA | 8BCE | mov ecx,esi |

2E22C0DC | FFD2 | call edx |

2E22C0DE | 5F | pop edi |

2E22C0DF | 5E | pop esi |

2E22C0E0 | 5B | pop ebx |

2E22C0E1 | 5D | pop ebp |

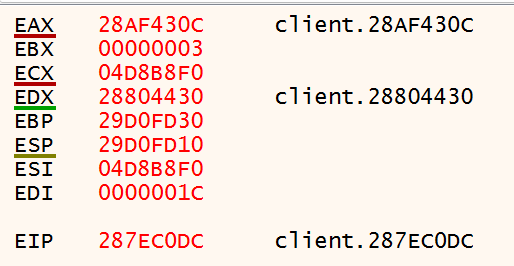

2E22C0E2 | C2 1400 | ret 14 |The call instruction at 0x2E22C0DC is the one that was triggered when the portal gun was fired. It naturally makes sense to set a breakpoint in x64dbg on this address. Doing so and navigating back to the game shows no effects. However, when the portal gun is fired, the breakpoint gets triggered, which lines up with what the Call Logger showed. When the breakpoint is hit, the following program state is present.

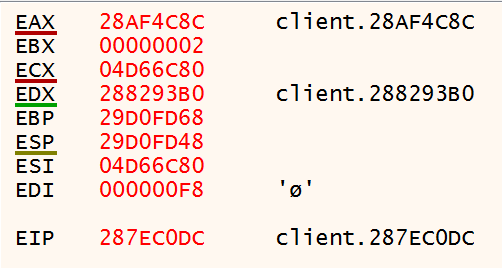

These registers don’t make much immediate sense, but EDI and EBX look interesting as they are the second and third arguments to the function and have integer values. Clicking to shoot several times shows that these values stay consistent. However, there is a change when you choose to shoot a blue portal versus an orange one (left click versus right click). Clicking the right mouse button to shoot gives the following values when the breakpoint gets hit:

The value in EBX has changed from 3 to 2, and the value in EDI has changed from 0x1C to 0xF8.

Looking up above, EBX and EDI are derived from what gets stored in EAX, which gets passed into the function that we’re looking at.

287EC0B8 | 8B45 10 | mov eax,dword ptr ss:[ebp+10] |

287EC0BB | 03C0 | add eax,eax |

287EC0BD | 03C0 | add eax,eax |

287EC0BF | 2BD8 | sub ebx,eax |

287EC0C1 | 03F8 | add edi,eax |

287EC0C3 | 85DB | test ebx,ebx |

287EC0C5 | 74 17 | je client.287EC0DE |But before getting side tracked further reverse engineering, the functionality of the Call Logger does seem to have been validated, and within around 5 minutes of playing around with it, the location of code responsible for handling a weapon fire event has been found. This is a rather quick discovery; the alternative usually being to set breakpoints on Windows APIs related to key presses and tracing from there to find the relevant application code.

The source code for the TED API, Call Logger, and other demo applications is available on GitHub. Visual Studio is used as the build IDE for the TED API and demo applications; the solution can opened in Visual Studio and 32 or 64-bit binaries can be built. As a prerequisite to building, a few external packages will need to be installed. The preferred way to do this is via vcpkg, and steps are shown to install the dependencies below:

git clone https://github.com/microsoft/vcpkg

.\vcpkg\bootstrap-vcpkg.bat

.\vcpkg install concurrentqueue:x64-windows-static

.\vcpkg install capstone:x64-windows-static

.\vcpkg install capstone[x86]:x64-windows-static

.\vcpkg install grpc:x64-windows-static

.\vcpkg install concurrentqueue:x86-windows-static

.\vcpkg install capstone:x86-windows-static

.\vcpkg install capstone[x86]:x86-windows-static

.\vcpkg install grpc:x86-windows-static

.\vcpkg integrate installThe Call Logger application is built with Qt 6 and can be loaded in Qt Creator (preferred), or built with CMake. A release version of the Call Logger for 32 and 64-bit applications can be found on the releases page of the TED GitHub repository.

Interesting article! How did you set breakpoints on all call instructions in Portal 2 though? I though about it, and disassembling the whole file seems necessary. Furthermore it couldn’t that lead to crashes if the disassembly was wrong?

Best Regards,

Peter

Comment by Peter — October 26, 2022 @ 4:35 AM

Hi Peter,

Yes, you are correct. To set the breakpoints I went through and disassembled all executable code sections in the running process (while all threads except the debugger were suspended). The code leverages Capstone Engine to do the disassembly.

Comment by admin — October 26, 2022 @ 10:22 AM